In this series of articles on the leopard to be featured over the coming months the authors will discuss the most widespread large cat in the world which is on the brink of extinction

The leopard is a widespread and adaptable large cat that is found in a variety of habitats around the world. However, the leopard is facing a number of threats, including habitat loss, fragmentation, and poaching. This series of articles will discuss the status of the leopard around the world, focusing on the nine subspecies that are currently recognized. The first article will focus on the African leopard, which is the most widespread subspecies of leopard.

With the recent sighting of a melanistic (black) leopard cub in Yala National Park, interest in the island’s apex predator– which happily never flags! – has again surged.

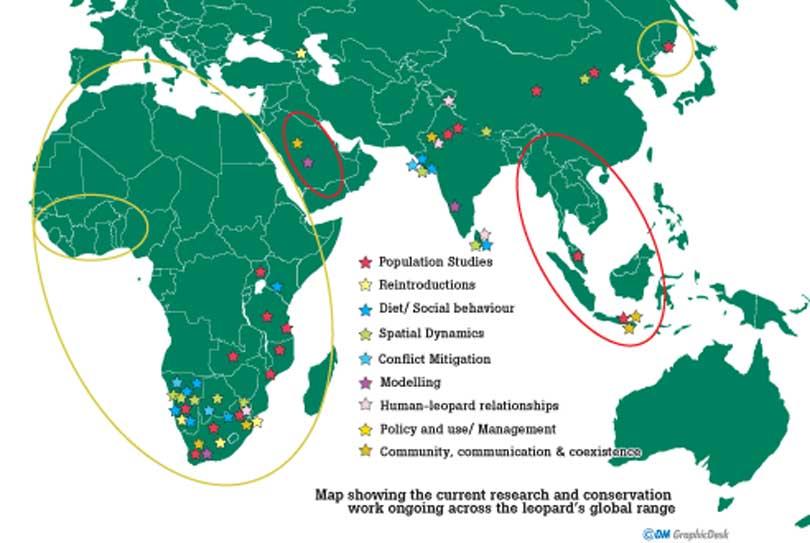

In March, the inaugural Global Leopard Conference (GLC) (leopardconference.org/), a virtual extravaganza of leopard research and conservation reporting from around the world was held, hosted out of South Africa.

We represented Sri Lanka, being asked to present three original research talks and honoured to have been asked to provide the wrap-up summary talk. With the nation’s favourite spotted (Or black!) cat in the news for the right reasons, the general interest in leopard conservation that exists in Sri Lanka, and the recently concluded GLC fresh in our minds, we thought this would be a good time to give an overview of the status of the leopard around the world, in Sri Lanka and the important role it plays for landscape conservation.

General Background

General Background

- The leopard (Pantherapardus) is considered to be the most adaptable of the big cats as it can survive across a vast range of habitat types and climatic conditions, from the arid Kalahari Desert of Namibia to the crushing cold of the Russian Far East; from the dense, moist lowland rainforests of the Malaysian Peninsula to barren, rocky outcrops of the Arabian Peninsula and up to the realm of the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) above 5000m in the Himalayas. One reason for this is the leopard’s catholic diet which sees it feed on more than 100 known species across the globe, ranging from giraffes to mice, although with an overall preference for medium size prey (About 25 kgs).

- Another of the leopard’s attributes is its ability to live close to humans, with well-known examples of this from Mumbai where a high density of leopards occupies the urban Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and Nairobi where animals regularly emerge from Nairobi National Park into city suburbs. Sri Lanka has its own version of this with the leopards of Kandy that are resident within the city limits in the Dunumadalawa Forest Reserve.

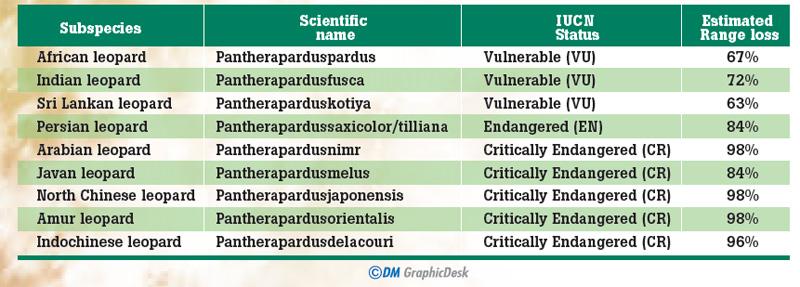

- Despite this adaptability however, the leopard has lost most (63 – 75%) of its historic global range and finds itself increasingly relegated to isolated patches of landscape. In addition to habitat loss and fragmentation, the leopard can run into conflict with people over livestock with retaliatory killing of leopards widespread globally.

- Additionally, the leopard is somewhat cursed by its own beauty with illicit demand for leopard skins – as well as bones and teeth – remaining a cause of population decline in some regions of the world.

- Due to this decline and ongoing persecution, the status of the species is considered Vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN Red List).

The Sri Lankan leopard (Pantherapardus kotiya) is one of nine genetically distinct subspecies of leopard that once roamed across the length and breadth of Africa and Asia.

For this series we summarize the current situation of each of the sub-species, drawing from the research updates during the Global Leopard Conference, 2023.

An update on the global status of leopards (Pantherapardus)

The Sub-species

We start with the African leopard, a subspecies that is found on this large, still wild continent. The leopard here, unlike in Sri Lanka, competes with a multitude of other predators within its guild, both large cats such as the lion as well as non-feline carnivores like the hyena or wild dog.

African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)

It is perhaps surprising that across the vast and varied continent that is Africa, there is only a single leopard sub-species. Perhaps if the now-extinct Zanzibar leopard which once inhabited the eponymous island off Tanzania’s coast, or Barbary leopard, which once roamed the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, were still around, their centuries of isolation from other populations would have ensured their genetic distinctiveness.

The status and situation of African leopards varies dramatically according to region and while all are essentially sub-Saharan (with possible remnant populations in Algeria and Egypt), the species is perhaps best divided into Western, Eastern, Southern and Central regional populations.

In West Africa, characterized by high human density, plantation economies and, increasingly, conflict, data is scarce and often entirely deficient with fragmented populations hanging on in a scattered matrix of Protected Areas (PA). This paucity of information was illustrated at the GLC with only a single presentation detailing research and conservation efforts across this entire region!

A key message was the increasing threat posed to wildlife due to armed conflict from N. Nigeria through Niger, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso etc.

In East Africa, the future for leopards appears to be more secure, although populations are currently understood to be restricted mostly to PAs in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda.

Throughout these savannah-dominated habitats – which hold some of the world’s most iconic National Parks such as Tanzania’s Serengeti and Kenya’s Maasai Mara – leopards typically co-exist with lions (Pantheraleo) and are therefore restricted to riparian habitats and dense bushland.

A substantial threat in these landscapes is from poaching, with the communities that surround PAs often impoverished and heavily reliant on bushmeat for sustenance. That PAs in many parts of East Africa are typically inaccessible to these local communities means that they are often viewed as little

more than a larder.

Community conservation initiatives are addressing this inequality and in some areas have been quite successful in integrating communities and conservation goals and allowing local groups to benefit economically and socially from the presence of PAs. Southern Africa has a lot of issues with livestock depredation across unprotected rangelands, with “problem” leopards frequently captured and trans-located – especially in Namibia and, slightly less so, South Africa. Translocations typically don’t work, with the re-located animal typically being put into an area with existing resident leopard populations and therefore having a lowered chance of success, and new leopards quickly colonizing the now available territory from where the “problem” animal was captured.

Before long, many of these colonizing leopards also start to predate the free-ranging livestock. In other parts of Southern Africa – Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique –

leopards still occur across numerous PAs.

Central African leopards are, if anything, even more data deficient than their West African counterparts, with inhospitable terrain, unstable political situations and ongoing conflict (e.g. Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic People’s Republic of the Congo) making efforts to understand leopard status very challenging.

Trophy hunting is another contentious issue in many parts of Africa with conservation outcomes heavily dependent on the integrity and scientific management of operators. Some hunting concessions manage a reasonable balance with sound management that sees minimal off-take of wildlife for maximum financial benefit, which is then fed back into longer-term ecosystem conservation.

Others, however, are more ad hoc in their approach and can upset ecosystem balance by taking too many animals or the wrong age/sex class of animals, usually driven by greed and a lack of wider consideration for wildlife. This can have very detrimental effects on wildlife populations and wider ecosystems. A lot of research effort is going into attempts to make the trophy-hunting arena sustainable to ensure that only older, no longer reproductive individuals are targeted as this has a much smaller impact on populations.

The sad reality in many parts of Africa is that in the absence of the profits generated from trophy hunting, the land would be quickly converted to agriculture which would be even more detrimental for wildlife. So while we are not personally keen on seeing animals killed solely to adorn the walls of the wealthy, we are also somewhat reticent to see trophy hunting banned outright for fear of the unintended consequences that may occur.

Perhaps rigorous regulation and careful oversight of hunting concessions, guided by good science, is the better short-term solution? Long term, a more viable solution that does not include trophy hunting is needed if the leopard as well as other big cats are to continue to survive across Africa.

© WWCT.org (2023). Wilderness & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Sri Lanka. All work by WWCT is conducted under the purview of and often in collaboration with the Department of Wildlife Conservation, Sri Lanka.

The sad reality in many parts of Africa is that in the absence of the profits generated from trophy hunting, the land would be quickly converted to agriculture which would be even more detrimental for wildlife

The sad reality in many parts of Africa is that in the absence of the profits generated from trophy hunting, the land would be quickly converted to agriculture which would be even more detrimental for wildlife

” An African leopard gracefully descending down a tree in the Serengeti- the leopards here are far more arboreal than in other parts of the world, given their subordinate role, due to heavy competition with other carnivores.”

IMAGE COURTESY : ANDREW KITTLE